PRACTICE-BY-DESIGN SERIES

In order to make better artistic and design choices, the Fluent and Empowered Designer should have answers to 5 essential questions. In this article, I present the fourth essential question: How Do I Evoke A Resonant Response To My Work?

Jason seemed to never be able to get past “That’s nice.” His clients always said, “That’s nice,” and that was about it.

His colors were balanced and harmonious. They fit rules about color schemes and color proportions. His placement of shapes and sizes were always pleasing to the eye. The little bit of math he had to do always checked out. His clients liked him.

They had approved the initial sketches. Their comments were positive. They never complained about his approach. But they were never satisfied enough for Jason to make that final sale.

Even though the feedback always seemed positive, he rarely had repeat business.

He was perplexed, and felt a little defeated.

What was it about his work that somehow fell short?

Jason was stuck with the impression that if someone said they liked something, that this would translate into them doing something more, like buying it. All designers need a firm and comprehensive understanding about the differences among like, need, want, demand, and parting with some money for it. Another way to put this is that designers need to recognize the differences between an emotional response and a resonant one. Designers should be able to answer these 5 essential questions, especially question 4: How Do I Evoke A Resonant Response To My Work?

Question 4: Beyond applying basic techniques and selecting quality materials, how do I evoke a resonant response to my work?

An artistic and well-designed piece or project should evoke, at the least, an emotional response. In fact, preferably, it should go beyond this a bit, and have what we call “resonance”. The difference between an emotional response and resonance is reflected in the difference between someone saying, “That’s beautiful,” from saying “I need to wear that piece,” or, “I need to buy that piece,” or, “I need to implement that project.”

Quite simply: If no resonant response is evoked, then the piece or project has some remaining issues including the possibility that it is poorly designed. Evoking a resonant response takes the successful selection and arrangement of materials or objects, the successful application of techniques as well as the successful management of skills, insights, and anticipating the client’s needs and understandings.

Every designer should have but one guiding star — Resonance. If our piece or project does not have some degree of resonance, we keep working on it. If the process of creative exploration and design does not lead us in the direction of resonance, we change it. If the results we achieve — numbers of pieces made and numbers of pieces sold — is not synced tightly with resonance, we cannot call ourselves designers.

The Proficient Designer specifies those goals about performance which will lead to one primary outcome: To Evoke Resonance. Everything else is secondary.

Materials, techniques and technologies are selected with resonance in mind. Design elements are selected and applied with that idea of Resonance in mind. Principles of Composition, Construction and Manipulation are applied with that idea of Resonance in mind, with extra special attention paid to the Principle of Parsimony — knowing when enough is enough.

People may approach the performance tasks in varied ways. For some this means getting very detailed on pathways, activities, and objectives. For others, they let the process of design emerge and see where it takes them. Whatever approach they take in their creative process, for all designers, a focus on one outcome — Resonance — frees them up to think through design without encumbrance. It allows them to express meaning. It allows them to convey expressions in meaningful ways to others.

This singular focus on resonance becomes a framework within which to question everything and try to make sense of everything. Make sense of what the materials and techniques can allow them to do, and what they cannot. Make sense of what understandings other people — clients, sellers, buyers, students, colleagues, teachers — will bring to the situation, when exploring and evaluating their work. Make sense of why some things inspire you, and other things do not. Make sense of why you are a designer. Make sense of the fluency of your artistic expression, what works, how it works, why it works.

We achieve Resonance by gaining a comfort and ease in communicating about design. This comfort and ease, or what we can call disciplinary fluency, has to do with how we translate our inspirations and aspirations into all our compositional, constructive and manipulative choices. It is empowering. Our pieces resonate. We achieve success.

Resonance, communication, success, fluency — these are all words that stand in place for an intimacy between the designer and the materials, the designer and the techniques, the designer and inspiration. They reflect the designer’s aspirations. They reflect the shared understandings of everyone the designer’s piece or project is expected to touch. They reflect the designer’s managerial prowess in bringing all these things together.

Evoking An Emotional Response vs. A Resonant One

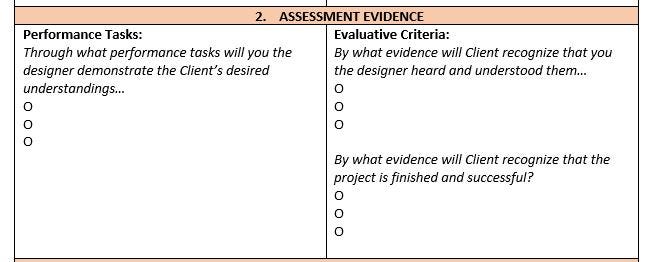

What is the evidence we need to know for determining when a piece or project is finished and successful? What clear and appropriate criteria hone in at what we should look at? What clues has the designer provided to let the various audiences become aware of the authenticity of the performance?

There are different opinions in craft, art and design about what are the most revealing and important aspects of the work, and which every authentic jewelry design performance must meet.

The traditional criteria used in the art world are that the designer should achieve unity with some variety and evoke emotions. These, I feel, may work well when applied to paintings or sculpture, but they are insufficient measures of success when applied to design. Design involves the creation of objects or projects where both artistic appeal as well as practical considerations of use are essential. Unity and variety can feel harmonious and balanced, but yet boring, monotonous and unexciting. Art, in contrast to Design, can be judged apart from its use and functionality. The response to Art can show some positive emotion without the client having to show any strong commitment. Design doesn’t share that luxury.

Finished and successful designed objects or projects not only must evoke emotions, but, must resonate with the user (and user’s various audiences), as well.

Achieving Resonance is the guiding star for designers, at each step of the way.

Resonance is some level of felt energy which extends a little beyond an emotional response. The difference between emotion and resonance can, for example, be like the differences between saying that piece or project is “Beautiful” vs. saying that piece or project “Makes me want to wear it”. Or that “I want to touch it.” Or “My friends need to see this.” Or “I need to implement this at once.”

Resonance is something more than emotion. It is some kind of additional energy we see, feel and otherwise experience. Emotion is very reactive. Resonance is intuitive, involving, identifying. Emotion is very sympathetic. Resonance is more of an empathetic response where artist and audience realize a shared (or contradictory) understanding without losing sight of whose views and feelings belong to whom.

Resonance results from how the artist controls light, shadow, and their characteristics of warmth and cold, receding and approaching, bright and dull, light and dark. Resonance results from how the artist leverages the strengths of materials, objects and techniques and minimizes their weaknesses. Resonance results from social, cultural and situational cues. Resonance results from how the artist takes us to the edge of universal, objective understandings, and pushes us ever so slightly, but not too, too far, beyond that edge.

Many people begin to explore design as a hobby, avocation, business or career. This requires, not only strong creativity skills, but also persistence and perseverance. A lot of the success in this pursuit comes down to an ability to make and follow through on many artistic and design decisions within a particular context or situation. Developing this ability — a fluency, flexibility and originality in design — means that the designer has to become empowered to answer these 5 essential questions: (1) whether creating something is a craft, an art or design, (2) how they think creatively, (3) how they leverage the strengths of various materials and techniques, and minimize weaknesses, (4) how the choices they make in any one design evoke emotions and resonate, and (5) how they know their piece is finished and successful.

Design is more than the application of a set of techniques. It is a mind-set. This fluency and empowerment enable the designer to think and speak like a designer. With fluency comes empowerment, confidence and success.

Continue reading about the Fifth Essential Question every designer should be able to answer: How Do I Know My Piece Is Finished?

The 5 Essential Questions:

1. Is What I Am Doing Craft, Art or Design?

2. What Should I Create?

3. What Materials (And Techniques) Work The Best?

4. How Do I Evoke A Resonant Response To My Work?

5. How Do I Know My Piece Is Finished?

Other Articles of Interest by Warren Feld:

Disciplinary Literacy and Fluency In Design

Backward Design is Forward Thinking

How Creatives Can Successfully Survive In Business

Part 2: The Second Essential Question Every Designer Should Be Able To Answer: What Should I Create?

Doubt / Self-Doubt: 8 Pitfalls Designers Fall Into…And What To Do About Them

Part 1: Your Passion For Design: Is It Necessary To Have A Passion?

Part 2: Your Passion For Design: Do You Have To Be Passionate To Be Creative?

Part 3: Your Passion For Design: How Does Being Passionate Make You A Better Designer?

Thank you. I hope you found this article useful.

Also, check out my website (www.warrenfeldjewelry.com).

Subscribe to my Learn To Bead blog (https://blog.landofodds.com).

Visit Land of Odds online (https://www.landofodds.com)for all your jewelry making supplies.

Enroll in my jewelry design and business of craft video tutorials online. Check our my video tutorials on DOING CRAFT SHOWS and on PRICING AND SELLING YOUR JEWELRY.

Add your name to my email list.

____________________________________

FOOTNOTES

Feld, Warren. The Goal Oriented Designer: The Path To Resonance. Art Jewelry Forum, 2018.

Feld, Warren. “Jewelry Design: A Managed Process,” Klimt02, 2/2/18.